Vicente Fernandez 15 Grandes Numero Uno Download

| Vicente Fernández | |

|---|---|

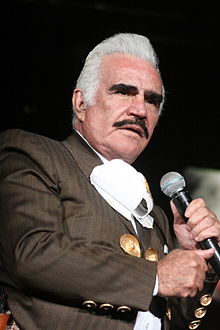

Fernández at Denver's Pepsi Eye in 2011 | |

| Born | Vicente Fernández Gómez (1940-02-17)17 Feb 1940 Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico |

| Died | 12 December 2021(2021-12-12) (anile 81) Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1952–2016 |

| Children | four, including Alejandro Fernández |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Labels |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Vicente Fernández Gómez (17 February 1940 – 12 December 2021) was a Mexican vocalizer, actor, and film producer. Nicknamed "Chente" (short for Vicente), "El Charro de Huentitán" (The Charro from Huentitán),[1] "El Ídolo de México" (The Idol of Mexico),[2] and "El Rey de la Música Ranchera" (The Rex of Ranchera Music),[three] Fernández started his career as a busker, and went on to get a cultural icon, having recorded more than than 50 albums and contributing to more than 30 films. His repertoire consisted of rancheras and other Mexican classics.

Fernández's work earned him three Grammy Awards,[4] nine Latin Grammy Awards, fourteen Lo Nuestro Awards, and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. He sold over 50 million copies worldwide, making him one of the best-selling regional Mexican artists of all time.[ii] In 2016, Fernández retired from performing live,[5] although he connected to record and publish music.[6]

Early on life [edit]

Vicente Fernández was born on 17 February 1940[2] in the village of Huentitán El Alto, Jalisco, the son of a rancher and a housewife.[7] When he was between half-dozen and vii years old, he used to go with his mother to meet movies starring Pedro Infante and Jorge Negrete and, as he himself once recalled, he told his female parent that "when I abound up I'm going to be similar them".[viii] Thereafter he had a gustation for music and at the age of viii he was given a guitar, which he learned to play at the same time he began to report folk music.[9]

Fernández's family unit found it difficult to back up themselves past selling milk from the cows on their ranch, and then later on Fernández finished elementary school he and his family moved to Tijuana. Once a teenager, Fernández began working various jobs, including as a bricklayer, painter, and cabinetmaker. During his working day he sang, so many structure companies asked to take him every bit a worker. Afterward these jobs he was hired to piece of work as a cashier in his uncle's restaurant. [10] At the age of fourteen he started singing in restaurants and at weddings, joining several mariachi groups such as Mariachi Amanecer de Pepe Mendoza and Mariachi de José Luis Aguilar. It was then when, in Jalisco, he participated in the radio program Amanecer Tapatío, and began to be recognized locally.[9] At the age of 21 he appeared on the television show La calandria musical. It was his first paid evidence.[xi]

On 27 December 1963 he married Maria del Refugio Abarca Villaseñor,[11] with whom he had his first son, Vicente, who was born premature and had to exist incubated at home because Fernández could not pay the hospital.[10] That yr, his 47-yr-old mother died of cancer.[12]

In 1965 he moved to Mexico Metropolis to seek a future in the world of music. His first attempts with the record companies were unsuccessful, considering it was the time of stardom for the vocaliser Javier Solís. There he bundled to sing in a plan of the radio network XEX-AM, which at that fourth dimension was the most important in the state. A few days afterwards the premature death of Solís in April 1966, Fernández received his first offers for albums.[viii] His kickoff contract was with CBS México, the recording label in the Mexican department of CBS Records International, for whom he recorded albums such as "Soy de Abajo", "Ni en Defensa Propia", and "Palabra de rey". Some of Fernández'south songs such every bit Tu Camino y El Mío and Perdóname were very successful.[9] [7]

Career [edit]

1970s and 1980s: Volver volver and Fernández's success [edit]

Fernández had to wait a decade to consolidate his career. With the decease in 1973 of José Alfredo Jiménez, one of the great icons of rancheras, Fernández became a reference point in the music industry.[13] His next anthology was La voz que estabas esperando and the post-obit albums, titled El rey, El hijo del pueblo, and Para recordar, sold millions of copies.[12]

In 1976, with the song Volver Volver, written in 1972 by Fernando Z. Maldonado, his fame was catapulted throughout the country and the American continent based on the sales of this recording.[nine] [10] [vii] That song came to exist covered more than twenty singers, including Chavela Vargas, Ry Cooder, and Nana Mouskouri.[14]

In the 1980s the style of Fernández's songs inverse from bolero ranchero to a ranchera focused on migration. In fact, the vocal Los Mandados was a reference to those Mexicans migrating to the Usa and reproduced manlike and patriotic stereotypes.[xiii] These were the years in which he congenital his ranch "Los 3 Potrillos", which would cease upwards being his music product center.[12] In 1983 he released his album 15 Grandes con el Numero Uno, which was the commencement to exceed one million copies sold.[15] In 1984 he gave a concert at the Plaza de Toros México, which was attended by 54,000 people.[15]

In 1987 he launched his showtime tour outside the United states of america and United mexican states when he traveled to Bolivia and Colombia.[16]

1990s: Fernández at his musical peak [edit]

The U.S. press in 1991 was already talking about Fernández as the "Mexican Sinatra" and he released ranchera classics such every bit Las clásicas de José Alfredo Jiménez (1990), Lástima que seas ajena (1993), Aunque me duela el alma (1995), Mujeres divinas, Acá entre nos, Me voy a quitar de en medio (1998), and La mentira (1998), which all became classics.[12]

In 1998 his elder son Vicente Jr. was kidnapped by the "Mocho Dedos", who demanded five one thousand thousand dollars as ransom. Afterwards Fernández Sr. paid $three.two million dollars to gratuitous him Vicente Jr. was abandoned outside the family ranch 121 days later with two of his fingers having been amputated. Fernández did all this without going to the constabulary; both he and his other son Alejandro continued to perform concerts to maintain the appearance of normalcy to the public. In 2008 the kidnappers were sentenced to 50 years in prison.[17] [18] [19]

2000s and early 2010s [edit]

In 2001 he launched the Lazos Invincibles tour, together with his son Alejandro.[fifteen] In 2006 Vicente Fernandez released the album La tragedia del vaquero, which was certified platinum in the United states of america.[fifteen]

He won a Latin Grammy again in 2008 with the album Para Siempre which was released in 2007. In 2008 he released Prime Fila, which was certified double platinum in Mexico, platinum in Central America, platinum in Colombia, and double platinum plus gold in the United States. The album remained seven consecutive weeks at number 1 on Billboard, and led him to win some other Latin Grammy for Best Ranchero Album.[20] [15]

The concert he performed at the Zócalo in Mexico City on 14 February 2009 broke attendance records, with almost 220,000 people gathered to hear him.[15] That aforementioned year he released the anthology Necesito de ti, which won a Grammy and a Latin Grammy the following twelvemonth.[xv] In September 2010 the album El Hombre Que Más Te Amó was released, produced past Vicente himself, for which he won a Latin Grammy again. He released Otra vez, as well produced by him, in November 2011.[15]

Subsequently the 2010 Haiti earthquake, Fernández was one of the fifty Latin singers who participated in the charity song "Somos El Mundo 25 Por Republic of haiti", a cover version of "We Are the Globe".[21]

Fernández started off the opening ceremony of the 2011 Pan American Games, hosted past Guadalajara, and sang "México Lindo y Querido" and "Guadalajara"; later in the ceremony he sang the Mexican national anthem before the parade of the athletes' delegations.[22] In October 2011, taking reward of his U.South. tour, he signed a three-yr agreement with Budweiser for the second fourth dimension to promote scholarships for Hispanic American students through the Hispanic Scholarship Fund.[23]

Afterwards years and retirement [edit]

On eight February 2012, he announced in a press conference, surprisingly, his intention to retire from the stage, just he specified that he would continue recording albums and that information technology was not due to health reasons only considering it was time to enjoy his work.[24] Two months later on, in the middle of a good day bout throughout the land and Latin America, he released the album Los 2 Vicentes, together with his son Vicente Jr.; the album included the theme song of the telenovela Amor bravío.[25]

Fernández performing at Estadio Azteca in Un Azteca En El Azteca retirement show in 2013

That same twelvemonth he recorded, together with Tony Bennett, Render to me at his ranch in Guadalajara for Bennett's album Viva Duets, in which Fernández sang in Spanish. In a later interview, Bennett said that Fernández had been "his favorite".[26] In 2012 he also released the album Hoy and won once more a Latin Grammy Honor in the 2013 edition. This was followed by the albums Mano a mano, tangos a la manera de Vicente Fernández, in 2014 (for which he won his 2d Grammy for All-time Regional Mexican Album and was nominated for a Latin Grammy for Best Ranchera Album),[27] and "Muriendo de amor", in 2015.[20]

On 28 Nov 2013 Fernández presented his book entitled Pero sigo siendo el rey in which he collects anecdotes and more than 2 hundred unpublished photographs about his professional person career.[28]

The farewell concert, titled "Un azteca en el Azteca" (An Aztec in the Aztec), took place on 16 Apr 2016 at the Estadio Azteca, in front of more than than fourscore,000 people; access was free. He sang more than 40 songs over more than four hours, the longest concert of his professional career. He only had 1 special guest, his son Alejandro.[29] [xxx] [31] The concert was collected on an album, with the aforementioned proper noun, for which Fernández won the Grammy Award for Best Regional Mexican Music Album in 2017.[twenty]

Despite retiring from the stage, he continued recording albums and songs, such every bit the album Más romántico que nunca in 2018 and A mis 80s in 2020, which earned him his 9th Latin Grammy Honor for all-time ranchera album in 2021.[30] [20]

In his 50-twelvemonth career he sold more 65 meg records and recorded more than 80 albums and more than than 300 songs.[32] [33]

Vicente Fernández's career as an histrion [edit]

Fernandez's debut in the movies was in 1971 with the film Tacos al carbón.[34] He starred in his beginning film in La ley del monte in 1976.[ix] During the 20 years he dedicated to acting, he starred in 30 films, xviii of which were under the direction of Rafael Villaseñor Kuri, and shared the stage with nationally renowned actors such as Blanca Guerra, Sara García, Fernando Soto, Resortes, and Lucía Méndez.[34] [35] In films such as Por tu maldito amor, La ley del monte, El hijo del pueblo, and Mi querido viejo, he introduced his music, so the title of the motion picture reflected the title of the song introduced. His main part was that of the stereotypical Mexican "manlike" and "gallant" man.[34]

Equally a film producer he debuted in 1974 with the film El hijo del pueblo. His last moving-picture show was Mi querido viejo, in 1991, and thereafter he devoted himself exclusively to music.[35]

Personal life [edit]

Controversies [edit]

Fernández sparked controversy after statements he made during an interview in May 2019 regarding his health. Fernández stated that he had been interned at a hospital in Houston, U.s.a. to undergo a liver surgery, but he decided to reject a transplant considering he did not "want to slumber with [his] wife while having the liver of another man, who could have been a homosexual or a drug user".[36]

In January 2021, Fernández sparked another controversy afterwards placing his hand on a fan's breast while taking a picture with her family.[37] A few days later, Fernández issued an apology to the woman's family, stating that "I admit that I was wrong, I don't know if I was joking, maybe information technology was a joke [...] I don't know. I exercise not remember, there were many people (with whom I took photos), sincerely I offer an apology".[38]

In Feb 2021, Fernández was accused of sexual assault past a singer named Lupita Castro.[39] [xl] Castro alleged that the incident had happened twoscore years prior, when she was 17, and that she had kept her silence because of the his influence and considering of his threats of violence against her. Castro refused to go to court against Fernández.[41]

Family [edit]

Fernández married María del Refugio Abarca "Cuquita" on 27 December 1963, the sister of a shut friend of his whom he met in his hometown. Three children were built-in from the union, Vicente Jr., Gerardo, and Alejandro and a 4th daughter, Alejandra, is his niece, whom they adopted. From their children they had 11 grandchildren and v great-grandchildren. Throughout his life he was accused past several persons of being unfaithful, which he always rejected.[42]

With his sons Alejandro and Vicente Jr, both singers, Vicente went on stage to sing with them on several occasions. The last time he went on stage was to sing with his son Alejandro, and to promote the musical career of one of his grandsons, Alex, in 2019.[43]

On the mean solar day of his death, his fortune was valued at $25 million.[44]

Health problems [edit]

Fernandez suffered from cancer on 2 occasions: in 2002 he overcame prostate cancer and in 2012 he had a tumor removed from his liver. In 2013 he suffered a thrombosis that caused him to lose his vocalisation temporarily and in 2015 he underwent surgery to remove abdominal hernias. He had chosen to refuse a liver transplant in 2012.[45] In 2021 he was admitted to the infirmary for two days to be treated for a urinary tract infection and was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome.[46]

Politics [edit]

Fernández was long associated with the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), which governed United mexican states from 1929 to 2000 and again between 2012 and 2018. Fernández was 1 of the many performers who participated in the "Solidaridad" campaign during the administration of Carlos Salinas de Gortari in the 1980s,[12] [47] and has also performed at PRI rallies, attended PRI events or met with politicians from that party; on one occasion, he performed the song "Estos celos" for then-President Enrique Peña Nieto (a PRI member) during an official celebration.[48] [49] [50]

He was invited at the U.S. 2000 Republican National Convention in Philadelphia to sing the famous Cielito lindo, simply ended up singing Los Mandados, considered an anthem for Mexican immigrants, generating criticism from those present.[51]

On 16 April 2016, at the end of his farewell concert, he cried out that he would "spit on" the then Republican Party primary candidate for the U.Due south. presidential election Donald Trump for his anti-immigration speech. Fernández, later on that twelvemonth, expressed his support for Hillary Clinton with a vocal titled "El Corrido de Hillary Clinton". Following the last argue between Clinton and Trump, Clinton invited Fernández to the commemoration at the Craig Ranch Regional Park Amphitheater, Las Vegas, U.South.[52]

Death [edit]

Fernández was hospitalized in serious condition later on falling at his ranch in Guadalajara on six August 2021.[53] He had injured his cervical spine and was placed on a ventilator nether the intensive care unit.[54] Ii weeks later he was diagnosed with Guillain–Barré syndrome and began treatment on thirteen August. His son Vicente confirmed to the press that information technology was a disease that had nix to do with the fall he suffered.[46] On 26 Oct 2021, he left intensive care following an improvement in his clinical condition.[55] On thirty November 2021, he was over again admitted to intensive care following a complication of his health caused by pneumonia. On 11 Dec, his son once again reported in an interview that his father was sedated due to a worsening of his condition.[56]

Fernández died of complications from his injuries on 12 December 2021, at the age of 81.[57] [58] [59] President of United mexican states Andrés Manuel López Obrador mourned his death with a tweet in which he recognized Fernández as the "symbol of the ranchera vocal of our time, known and recognized in Mexico and abroad". The Colombian president, Iván Duque, said "his departure hurts u.s. and his legacy will be alive forever", the U.Southward President, Joe Biden, said that "the world of music has lost an icon". Also on Twitter, leaders including the President of Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro, the Mayor of Mexico City, Claudia Sheinbaum, the former President of Colombia Álvaro Uribe, and of Republic of bolivia Evo Morales equally well as numerous Mexican and Latin American entertainment personalities offered their condolences.[60] Former U.S Secretary of State Hillary Clinton recognized Fernandez as "a musical icon and a good human being".[61] He died on the twenty-four hour period of Our Lady of Guadalupe, patron saint of Mexico, to whom Fernández had a great devotion.[62]

Fernández's body was transferred from the funeral home to the Arena VFG, which the creative person had donated to his urban center of Guadalajara, where his family and at least six thousand fans were already waiting for him. Songs including "El Rey" and "Acá Entre Nos" were performed by his Mariachi Azteca.[63] In that location the bury with his remains was placed, in the centre of the stage that was turned into an chantry with a big crucifix presiding over the scene and on ane side an prototype of the Our Lady of Guadalupe accompanied the coffin. On the coffin, which was surrounded by a sea of white flowers, rested his favorite sombrero.[64]

The following day the Catholic funeral took identify at the same loonshit. The anniversary was alternated past songs of his most famous rancheras and ended with "Volver volver", as he had wished, live. Afterwards, his body was taken to his ranch, where he was buried in a mausoleum.[65]

Awards and nominations [edit]

Fernández at a concert in Colombia, 2012

In 1990, Fernández released the album Vicente Fernandez y las clásicas de José Alfredo Jiménez, a tribute to Mexico'due south famous songwriter from Guanajuato known as The "God of Ranchera Music" José Alfredo Jiménez, who was also his main musical influence. The anthology earned him Billboard and Univision's Latin Music Accolade for Mexican Regional Male Artist of the Year, which he won five times from 1989 to 1993.[66]

In 1998, Fernández was inducted into Billboard 's Latin Music Hall of Fame.[67] On 11 November 1998 his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame was unveiled.[68]

In 2002, the Latin Recording University recognized Fernández as Person of the Yr.[69] That year he celebrated his 35th anniversary in the entertainment industry, a career in which he sold more than 50 1000000 records and was inducted into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame.[lxx] He has 51 albums listed on the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) for gold, platinum, and multiplatinum-selling records.[71]

Fernández also has an arena in Guadalajara named in his honour built in 2005 by his company,[72] and a star placed with his paw prints and proper name at the Paseo de las Luminarias in Mexico Urban center.[73] Governor of New Mexico, U.Due south Neb Richardson on 16 July 2008, alleged 12 June as Vicente Fernández Day in the country.[74] In 2010, Fernández was awarded his beginning Grammy Honor for Best Regional Mexican Anthology for his tape Necesito de Tí.[75]

In 2012, Chicago gave Fernández the key to the urban center and renamed the Little Hamlet neighborhood'due south Due west 26th Street in his honor. In improver, the city celebrates "Vicente Fernandez Week" from twenty to 27 October.[76] [77]

On six Oct 2019 in Guadalajara Fernández unveiled a statue created in his honor at the "Plaza de los Mariachis".[78]

Grammy Awards [edit]

The Grammy Awards are awarded annually by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences of the United States. Fernández received 3 awards from thirteen nominations.[4]

^[I] Each year is linked to the article about the Grammy Awards held that yr.

Latin Grammy Awards [edit]

The Latin Grammy Awards are awarded annually past The Latin University of Recording Arts & Sciences of the Us. Fernández received eight awards from fourteen nominations and besides earned the Latin Recording Academy for Person of the Year.[92]

^[I] Each yr is linked to the article about the Latin Grammy Awards held that year.

Lo Nuestro Awards [edit]

The Lo Nuestro Awards is an awards show honoring the best of Latin music, presented by boob tube network Univision. Fernández received fourteen awards from 30-three nominations.[95]

^[I] Each year is linked to the article about the Lo Nuestro Awards held that year.

Honours [edit]

- Orden Libertadores y Libertadoras de Venezuela (Venezuela, 2012)[10]

Discography [edit]

Filmography [edit]

Sources: [34] [96]

- 1991: Mí Querido Viejo (My Dear Old Human)

- 1990: Por Tu Maldito Amor (For Your Damned Love)

- 1987: El Cuatrero (The Rustler)

- 1987: El Diablo, el Santo y el Tonto (The Devil, the Saint, and the Fool)

- 1987: El Macho (The Tough One)

- 1987: El Embustero (The Liar)

- 1985: Entre Compadres Te Veas (You Find Yourself Among Friends)

- 1985: Sinvergüenza Pero Honrado (Shameless Merely Honorable)

- 1985: Acorralado (Cornered)

- 1985: Matar o Morir (Impale or Dice)

- 1983: Un Hombre Llamado el Diablo (A Homo Chosen the Devil)

- 1982: Juan Charrasqueado & Gabino Barrera

- 1981: Una Pura y Dos Con Sal (One Pure and Two with Salt)

- 1981: El Sinverguenza (The Shameless One)

- 1981: Todo un Hombre (Fully Manly)

- 1980: Como United mexican states no Hay Dos (Similar Mexico There Is No Other)

- 1980: Picardia Mexicana Numero Dos (Mexican Rogueishness Number Ii)

- 1980: Coyote and Bronca (The Coyote and the Problem)

- 1979: El Tahúr (The Gambler)

- 1977: Picardia Mexicana (Mexican Rogueishness)

- 1977: El Arracadas (The Earringer)

- 1975: Dios Los Cria (God Raises Them)

- 1974: Juan Armenta: El Repatriado (Juan Armenta: The Repatriated 1)

- 1974: El Albañil (The Bricklayer)

- 1974: La Ley del Monte (The Law of Wild)

- 1974: Entre Monjas Anda el Diablo (The Devil Walks Between Nuns)

- 1974: El Hijo del Pueblo (Son of the People)

- 1973: Tu Camino y el Mio (Your Road and Mine)

- 1973: Uno y Medio Contra el Mundo (One and a One-half Against the World)

- 1971: Tacos Al Carbón (Grilled Tacos)

References [edit]

- ^ Bonacich, Drago. "Vicente Fernández, Jr. | Biography & History". allmusic.com. AllMusic. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Jeff Tamarkin (Rovi Corporation). "Vicente Fernández – Biography". Billboard. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved xv Baronial 2012.

- ^ Tamarkin, Jeff. "Vicente Fernández | Biography & History". allmusic.com. AllMusic. Retrieved 21 Feb 2021.

- ^ a b "Vicente Fernandez". National University of Recording Arts and Sciences. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Jesse Katz (12 December 2021). "Vicente Fernández, a Mexican musical icon for generations, dies at 81". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Jessica Roiz (ten August 2018). "Vicente Fernandez Is Dorsum to Restore Your Faith in Dear With New Album 'Mas Romantico Que Nunca': Listen At present". Billboard. Retrieved 12 Dec 2021.

- ^ a b c Osorio, Camila (12 December 2021). "Muere el último rey del mariachi, Vicente Fernández". El País (in Spanish).

- ^ a b Martínez Polo, Liliana (12 December 2021). "La ranchera: la música en la que Vicente Fernández reinó por décadas". El Tiempo (in Spanish).

- ^ a b c d e ""Pero sigo siendo el rey..." Vicente Fernández, 'El Charro de Huentitán' que conquistó México con su voz". Milenio (in Spanish). 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Muere Vicente Fernández, el último gran cantante de rancheras de México". BBC (in Spanish). 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Vicente Fernández Biography". Sortmusic.com. Retrieved 13 Nov 2015.

- ^ a b c d east Civita, Alicia (12 December 2021). "Muere Vicente Fernández, la leyenda que desafió a la Historia, a los 81 años". Los Ángeles Times (in Spanish).

- ^ a b Osorio, Camila (13 Dec 2021). "El inmortal legado de Vicente Fernández en la industria musical". El País (in Castilian).

- ^ ""Volver, volver", la dramática historia de la canción más escuchada de Vicente Fernández en Republic of colombia". Infobae (in Spanish). 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h "Larga vida a "El Charro de Huentitán"". El Informador (in Spanish). 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernandez estrena disco este martes". La Chicuela (in Castilian). 21 Nov 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ News, Deseret (26 September 1998). "Kidnapping won't drive Fernandez from Mexico". Deseret News . Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández y el momento más doloroso de su vida: cuando secuestraron a su hijo y debió cantar para no llorar". El Comercio (in Castilian). 12 December 2021.

- ^ "El dolor más profundo de Vicente Fernández: secuestraron a su hijo y le quitaron dos dedos". El Heraldo (in Spanish). 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d Press, Associated (12 Dec 2021). "Los discos y películas de Vicente Fernández". Los Ángeles Times (in Spanish).

- ^ fifty Latin Stars Gather to Record "Somos El Mundo" – Billboard.com

- ^ "De Guadalajara para el mundo, uno de los eventos más impactantes del año: la gran inauguración de los Juegos Panamericanos 2011". ¡Hola! (in Spanish). 18 October 2011.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández continúa gira para promover educación para latinos". ¡Hola! (in Castilian). 31 October 2011.

- ^ Orozco, Gisela (9 February 2012). "Vicente Fernández anuncia su retiro de los escenarios". Chicago Tribune (in Spanish).

- ^ "Vicente Fernández estrena videoclip Cuando manda el corazón". El Informador (in Spanish). 11 September 2012.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández se retira del escenario pero no de la música". Prensa Libre (in Spanish). 15 April 2016.

- ^ "The Total Listing of Nominations Latin Grammy". Los Angeles Times. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández presenta united nations libro con anécdotas y fotografías inéditas". ¡Hola! (in Spanish). 29 November 2013.

- ^ "Más de twoscore canciones y muchos shots de tequila: así fue el último concierto de Vicente Fernández". El Universal (in Spanish). 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b "El día que Vicente Fernández se retiró en el Estadio Azteca ante miles de personas". Milenio (in Spanish). 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández: ¿Cómo fue su concierto de despedida en el Azteca?". El Financiero (in Spanish). fifteen April 2016.

- ^ Civita, Alicia (12 December 2021). "La huella musical de Vicente Fernández es más profunda de la que todos creen". Los Angeles Times (in Castilian).

- ^ "Muere Vicente Fernández: 7 de las canciones más emblemáticas del "rey de las rancheras"". BBC in Spanish (in Spanish). 12 Dec 2021.

- ^ a b c d López, Adolfo (12 Dec 2021). "Vicente Fernández, estrella de su cinematics". El Sol de México (in Spanish).

- ^ a b Salgado, Ivett (12 December 2021). "Más allá de la música: La huella de Vicente Fernández en el cine". Milenio (in Spanish).

- ^ "Vicente Fernández rechazó trasplante de hígado por temor a que fuera de un homosexual o drogadicto". El Universal. 8 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Daniel, Arzu (23 Jan 2021). "Silence Is Broken By A Fan Touching Vicente Fernandez's Chest". Amico Hoops . Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ ""Acosar es que yo le haya bajado la blusa": así respondió Vicente Fernández al escándalo del video con su seguidora" ["Harassing is that I have lowered her blouse": this is how Vicente Fernández responded to the scandal of the video with his follower]. Infobae (in Spanish). 26 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Me hizo algo más grave: Lupita Castro acusa a Vicente Fernández de acoso sexual y censura" ["He did something worse to me: Lupita Castro accuses Vicente Fernández of sexual assault and censure]. Milenio (in Spanish). 15 December 2021.

- ^ "Mexican singer Lupita Castro denounces Vicente Fernández for allegedly harassing her". Mundo Hispanico. 8 Feb 2021. Retrieved xv December 2021.

- ^ "Lupita Castro se niega a presentar un proceso legal en contra de Vicente Fernández tras acusarlo de abuso sexual: "No tengo el corazón"" ["Lupita Castro refuses to begin a legal process confronting Vicente Fernandez after accusing him of sexual abuse: "I don't have the eye to"]. Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández amó sólo una mujer de forma incondicional: su esposa, así fue su historia". Infobae (in Spanish). 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández, su última presentación en vivo junto a su hijo y nieto". ¡Hola! (in Castilian). 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Esto es lo que se sabe sobre la fortuna de Vicente Fernández y quiénez la herederán". ¡Hola!. 12 December 2021.

- ^ Aviles, Gwen. "Singer Vicente Fernández refused transplant, feared donor a 'homosexual or an addict'". NBC News . Retrieved 13 Dec 2021.

- ^ a b "Vicente Fernández padece el síndrome de Guillain-Barré". Los Angeles Times (in Spanish). 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Solidaridad Official Song". YouTube. Archived from the original on xiii December 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández le canta a Peña Nieto 'Estos celos'". Vertigo Politician. 19 February 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Coming together betwixt a PRI candidate and Fernández". Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Quiroz, Carlos. "Comienza transformación de Jalisco: Aristóteles Sandoval". Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Gurza, Agustin (12 Dec 2021). "GOP Didn't Come across Their Sweet Serenader'southward Other Side". LA Times.

- ^ ""Gracias, Chente"; recuerdan canción de Vicente Fernández en campaña de Hillary Clinton". El Universal (in Spanish). 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández in 'Serious But Stable' Condition After Astringent Autumn". Entertainment Weekly . Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández news: Legendary Mexican vocaliser on ventilator in ICU after fall". ABC. 10 August 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández abandona terapia intensiva y es trasladado; Alejandro le mandó united nations mensaje". Los Angeles Times (in Spanish). 27 October 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández: la complicación que lo llevó a ser sedado, según reveló el más reciente reporte médico". Infobae (in Castilian). 11 Dec 2021.

- ^ Chung, Christine (12 Dec 2021). "Vicente Fernández, 'El Rey' of Mexican Ranchera Music, Is Expressionless at 81". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández, king of Mexican ranchera music, dies at 81". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Muere el cantante Vicente Fernández a los 81 años". El Heraldo. 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Así reacciona el mundo a la muerte de Vicente Fernández". CNN in Spanish. 12 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández: Hillary Clinton envía condolencias por el fallecimiento del "Charro de Huentitán"". El Informador. 13 Dec 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández, devoto de la virgen María, murió en el día de su fiesta". El Tiempo. xiii December 2021.

- ^ "Aquí dan el último adiós a Vicente Fernández". Los Ángeles Times. 12 Dec 2021. Retrieved 13 Dec 2021.

- ^ "Aquí dan el último adiós a Vicente Fernández". Los Ángeles Times. 12 December 2021. Retrieved 13 Dec 2021.

- ^ "'Viva Vicente Fernández para siempre': Así fue el sentido y apoteósico adiós al ícono de la música mexicana". Univision. 13 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernandez Biography". Musicianguide.com. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Burr, Ramiro (25 July 1998). "Hats Off to the Music of Regional Mexican". Billboard. Vol. 110, no. 30. p. 49. Retrieved xi Apr 2014.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández sigue siendo "El Rey" en Hollywood y estas fotos lo demuestran". Univisión (in Spanish). 12 December 2021.

- ^ "GRAMMY Rewind: Watch A Suave Vicente Fernandez Thank All Of Latin America At The tertiary Latin GRAMMY Awards". Grammy Awards. 24 September 2021.

- ^ "International Latin Music Hall of Fame Announces Inductees for 2002". 5 April 2002. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández. RIAA". RIAA.

- ^ "Esta es la Loonshit VFG, donde se dará el último adiós a Vicente Fernández". 24-horas.mx. 12 December 2021.

- ^ Pérez, Verónica (7 July 2021). "Lucero y Mijares fueron honrados en la Plaza de las Estrellas; fallece su creadora". Encancha.mx.

- ^ "Declaran día de Vicente Fernández en EU". El informador (in Spanish). 16 July 2008.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández gana su primer Grammy anglo". Terra Networks Mexico. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ Orozco, Gisela (22 October 2012). "Vicente Fernández, el homenaje en Chicago". Chicago Tribune (in Spanish).

- ^ Bautista, Berenece; Goodman, Sylvia (12 December 2021). "Vicente Fernández, revered Mexican singer known for his command of the ranchera genre and his elegant mariachi suits, dies at 81". Chicago Tribune . Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández develó una estatua en su honor, pero las redes sociales estallaron porque no se parece a él". Infobae. 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Complete List of the Nominees for 26th Almanac Grammy Music Awards". Schenectady Gazette. The Daily Gazette Company. 9 January 1984. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Listing of Grammy nominations". Times-News. Hendersonville, Due north Carolina. 11 January 1991. Retrieved 24 Feb 2015.

- ^ "36th Grammy Awards – 1994". Rock on the Cyberspace. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "The 37th Grammy Nominations". Los Angeles Times. six Jan 1995. p. three. Retrieved five March 2015.

- ^ "The Complete List of Nominees". Los Angeles Times. eight Jan 1997. p. 4. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "University's Consummate Listing of Nominees". Los Angeles Times. 6 January 1999. p. 4. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "A Complete Listing of the Nominees". Los Angeles Times. 5 January 2000. p. 4. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (4 January 2001). "Grammys Cast a Wider Net Than Usual". Los Angeles Times. p. 4. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "Complete Listing Of Grammy Nominees". CBS News. four January 2002. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Elizalde y K-Paz nominados al Grammy". Terra Networks (in Spanish). Telefónica. Associated Press. 6 December 2007. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández gana su primer Grammy anglo". Terra Networks Mexico (in Spanish). Telefónica. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Vulpo, Mike (viii February 2015). "2015 Grammy Award Winners: The Complete Listing". Eastward!. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ "Hither Is the Consummate Listing of Nominees for the 2017 Grammys". Billboard . Retrieved 8 Dec 2016.

- ^ Latin Grammy Awards:

- General Past Winners Search: "Past Winners Search". The Latin Grammys. The Latin Recording Academy. Retrieved twenty February 2015.

- ^ "The Full List of Nominations Latin Grammy". Los Angeles Times. 20 Nov 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Latin Grammy Awards 2021". CNN. 19 November 2021.

- ^ Lo Nuestro Awards:

- "Lo Nuestro 1989 – Historia". Univision (in Spanish). Univision Communications, Inc. 1989. Archived from the original on 17 Oct 2013. Retrieved ix September 2013.

- "Lo Nuestro 1990 – Historia". Univision (in Spanish). Univision Communications, Inc. 1990. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved iv September 2013.

- Lannert, John (1 June 1991). "Latin Music Finds Harmony in Awards Well-baked, Entertaining Tv Program A Breakthrough For Fledgling Trade Grouping". Sunday-Sentinel . Retrieved sixteen August 2013.

- Lannert, John (24 May 1991). "Hispanic Music Industry Salutes Its All-time Midweek". Dominicus-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 16 Baronial 2013.

- Lannert, John (28 Nov 1998). "Ana Gabriel Captures 4 Latin Awards". Billboard. Vol. 104, no. 22. p. 10. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- Lannert, John (30 March 1993). "Secada Lead Latin Noms Post-obit Grammy Win". Billboard. Vol. 105, no. x. p. 10. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- "Lo Nuestro 1993 – Historia". Univision (in Spanish). Univision Communications, Inc. 1993. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- "Univision Announces the Nominees for Spanish-language Music's Highest Honors Premio Lo Nuestro a la Musica Latina". Univision. 27 March 1996. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "Premios a Lo Mejor De La Música Latina". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Casa Editorial El Tiempo S.A. viii April 1997. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Barquero, Christopher (1998). "Premios Lo Nuestro: Los galardones a la música latina serán entregados en mayo próximo". La Nación (in Spanish). Grupo Nación GN, S.A. Archived from the original on xv June 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "¿Quiénes se llevarán esta noche el Premio Lo Nuestro "99?". Panamá América (in Spanish). Grupo Epasa. 6 May 1999. Archived from the original on fifteen June 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- "Lo Nuestro tiene sus candidatos". La Nación (in Castilian). La Nación, S.A. de C.Five. 15 April 2012. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- "Seis nominaciones para Son by Four". Que Pues (in Spanish). Grupo Editorial Zacatecas, S. A. de C. V. 9 January 2001. Archived from the original on xvi June 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- "Premios Lo Nuestro: Votación 2001". Univision. Univision Communications Inc. 2001. Archived from the original on 29 Nov 2014. Retrieved fourteen August 2013.

- "Premios Lo Nuestro: Alfombra Roja: Lista completa de los ganadores de Premio Lo Nuestro 2001". Univision. Univision Communications Inc. 2001. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Premios Lo Nuestro a la Musica Latina: Lo que fue Lo Nuestro en 2002". Univision. Univision Communications Inc. 2002. Archived from the original on xiii October 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Premios Lo Nuestro: Votación Video del Año". Univision. Univision Communications Inc. 2002. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- "Univision Announces Winners of Premio Lo Nuestro 2003". Business organization Wire. Gale Group. 6 February 2003. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "Ricky Martin, Shakira, Thalia and Juanes Among Superstar Nominees for Premio Lo Nuestro 2004 Latin Music Awards". Business organisation Wire. Gale Group. 14 Jan 2004. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- "And the nominees are..." Univision. Univision Communications Inc. 2005. Retrieved 24 Baronial 2013. [ permanent expressionless link ]

- "Ganadores de los Premios Lo Nuestro 2006". Terra. Telefónica. 23 February 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- "Montez de Durango y Marc Anthony lideran Premio Lo Nuestro". People. 12 Dec 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2013. [ permanent dead link ]

- "Halaga a Vicente Fernández Premio Lo Nuestro a la Excelencia". El Informador (in Castilian). Unión Editorialista. viii Feb 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "Ganadores de premios Lo Nuestro 2009". Sipse (in Spanish). 28 March 2009. Archived from the original on 13 September 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- López, Diego (Feb nineteen, 2010). "Aventura se lleva la noche en los Premios Lo Nuestro 2010". Yahoo! (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 12, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- "Sony Music Nominees for Premio Lo Nuestro 2010". SML Printing (in Spanish). 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- Alonzo, Fabricio (February 6, 2012). "Lista de nominados a los premios Lo Nuestro 2012". Starmedia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on December 15, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- "Premios Lo Nuestro 2013: estos son los ganadores". El Comercio (in Spanish). 22 February 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "List of Nominees Premio Lo Nuestro Latin Music Honor 2014" (PDF). Univision. Univision Communications. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 Dec 2013. Retrieved 9 Dec 2013.

- ^ "Vicente Fernández en el cinematics: '¿en qué películas actuó el "charro de Huentitán"?'". CNN. 12 December 2021. Retrieved 13 Dec 2021.

External links [edit]

- Sony Music

- Vicente Fernández discography at Discogs

- Vicente Fernández at IMDb

DOWNLOAD HERE

Posted by: lynharms1991.blogspot.com

0 Comments